Story

Releasing Jargon for Innovation: Reframing the Language of Improvement

In my fourth year in education, our superintendent championed the word lagniappe as our staff mantra. At district-wide meetings, in e-blasts, and in all staff communication, he would remind us to embrace lagniappe as part of our daily routines. The word was deeply personal to him and, in turn, was meant to inspire staff to go the extra mile.

Lanyards and stickers were given on professional development days, and lagniappe was plastered on social media. It was the mindset we were meant to embrace as part of our staff identity. But, like several others, I had no idea what it meant or how to pronounce it. Many of us wore lagniappe on our school badges because it was a fun phrase, but we had no clue about what we were trying to embody.

I have since learned that lagniappe, pronounced lawn-yop, is a Cajun-French word meaning a little extra on purpose. This beautiful sentiment was completely lost on me while working in the district.

Identify Jargon

Although an atypical phrase in most of the K12 space, lagniappe is not unlike other education jargon. Too often, we use buzzwords and professional-speak to describe school improvement work without pausing to understand what those words mean in practice.

Moreover, school improvement can be overburdened by negativity just by the words chosen to describe the process and outcomes. Words like “compliance” and “mandate” can muddy the purpose of the work, leading to confusion rather than innovation.

How can teams overcome this confusion?

Start by naming and defining the words that impede collaboration.

Build a Glossary of Shared Language

Through discussion, invite team members to share words and phrases that reinforce compliance and accountability mindsets for them. Maybe it’s something as unique as lagniappe or as common as fidelity. Whatever the case may be, use your list to gain insight into how shared language shapes shared work.

As your team identifies terms, note why these words may not align with innovation and what words could be used instead. Use these prompts to guide your thinking:

- What mindset might this word or phrase evoke?

- How might that work against the innovation mindset we want to create across our team?

- What’s the word or phrase that would evoke an innovation mindset that could be used in place of the original?

Commit to Shifts

As you assess your shared language, be intentional in your follow-through and commit to reframing your shared words. Use these three prompts to help implement your new glossary and sustain these new shifts:

- What are some upcoming opportunities to practice these shifts in language?

- What will you and your team do to reinforce the use of words that support your innovation mindset?

- Determine a time to revisit the glossary you’ve created.

Download our tool, Reframing The Language of Improvement, for a complete facilitation guide and glossary template.

Building Sustainable Leadership Practices

When I’m not working, I’m often running — for exercise or after a young child – and I’ve had my share of injuries, including a pulled hamstring that wouldn’t heal. When I complained to the doctor, she shook her head at me.

“Look,” she said, “the hamstring is actually a bundle of muscles. The way you’re moving yourself forward is using some of them more than others. Until you’ve got them all engaged equally, you’ll be hurting. And you won’t be running — at least not as fast as you want to.”

Running the change leadership race

Aches and pains in moving forward — and struggles to move forward at all — are an everyday challenge for education professionals and for some of the same reasons. No matter the role, we’re charged with moving others from point A to point B. We change how students engage with content and master the work of learning, how fellow practitioners guide young and professional learners, and how fellow leaders exercise sound judgment.

Put another way, moving change forward is our work.

But that doesn’t make it easy. Whether it’s greater emerging needs among student enrollment, staffing shortages and budget cuts that ask public schools to do more with less, new faces on a team, or rapid shifts in standards and other mandates, it all adds up to nearly constant pressure for educators to make complex shifts in how they do every aspect of their work.

Fatiguing the muscles of leadership

The pace of these changes can be difficult to manage and sustain — sort of like trying to run a half marathon on a hurt leg. In fact, 70 percent of change efforts fail due to isolation from a supportive team, conflicting priorities, confusion about why change is happening or what it looks like, and a lack of individual or collective efficacy in navigating the change.

Schools and districts often tend to resort to single solutions and single leaders to turn things around. The idea is that pushing on the same programs and people will accelerate progress toward a goal even though the change failure rate and the rising frustration levels among teachers and administrators show us we’re wrong.

Pressing on the same “muscles” to power change over and over again while others atrophy is a recipe for slowdown or worse. And it’s not as if we have a shortage of options. With one in every four teachers ready to take on school-wide leadership work alongside teaching, schools and school systems have lots of leadership “muscles” they can engage. We know collective efficacy is a key to instructional improvement, and research shows that engaging educators in collective leadership is the key to sustaining transformational change in schools.

Moving forward together

So where do we start? At Mira Education, we find that the educators and leaders who are successful make three big shifts to retrain those leadership “muscles” so they work better together:

- From leaders to leadership.

Traditionally, leadership development has been about developing individual leaders, usually administrators. Given high rates of turnover in these positions, it’s difficult to see the path to ROI or sustainability in that approach. In fact, three-quarters of all principals agree their work is too complex to be done by a single individual anyway. Stone Creek Elementary and others with which Mira Education has worked think about how they develop larger and more robust teams to share the leadership load. That way, if one leader leaves, change doesn’t lose its momentum because every leader creates more leaders. - From compliance culture to rethinking resources.

Every school and district lives with mandates to implement programs, manage budgets, and fill Full Time Equivalencies (FTEs), each of which can feel siloed at best and incoherent at worst. Good leadership manages them well, but great leadership figures out how to reorganize them into a coherent whole. Led by a team of administrators and teachers, Walker-Gamble Elementary did just that. Today, every teacher at Walker-Gamble has at least five hours of weekly learning and collaboration time, staff report increased collective efficacy, and students are meeting both their own learning goals and state standards. - From siloed to networked.

These schools didn’t learn how to build this kind of capacity or get this kind of results on their own. They learned from one another. Teachers and administrators from each school’s leadership team visited partner schools as part of a network hosted by Mira Education. Likewise, we partnered with Northwest Independent School District (ISD) to help them find more effective ways for schools to set goals aligned with the district strategic plan and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) goals, break down barriers to collaboration among schools, and engage more of their staff in ongoing innovation and improvement efforts.

We know through these partnerships and others that collective leadership works where traditional improvement programs have not. And we know that teachers and administrators are equally important in putting practices in place to create sustainable educator leadership pipelines that have been challenging to build in other ways. But we also know that it takes many, many more stories of those successes to make a movement. Otherwise, we’re working with lone runners instead of a real race.

What is your school or district doing to build the power of teachers and administrators to lead collectively? Find tools and insights to power your work on our website, and share what works with us via social media using the #collectiveleadership hashtag.

I Remember, I Believe: One Teacher’s Networking Journey

The educators who taught and shaped me in my first years of schooling back in Detroit were Black teachers from the South, most of whom had been displaced by the South’s massive resistance backlash to the Brown decision. Along with the adults in my family, they gave me a love of education. That’s why as a new teacher in 1990, I was deeply troubled by the dissonance between those formative experiences and the stereotypes in popular culture (and within my teacher education program) of Black students as perpetually at-risk of academic failure, along with caricatures of Black educators as inherently inept. Networking with other teachers helped me confront those stereotypes and changed the course of my own career.

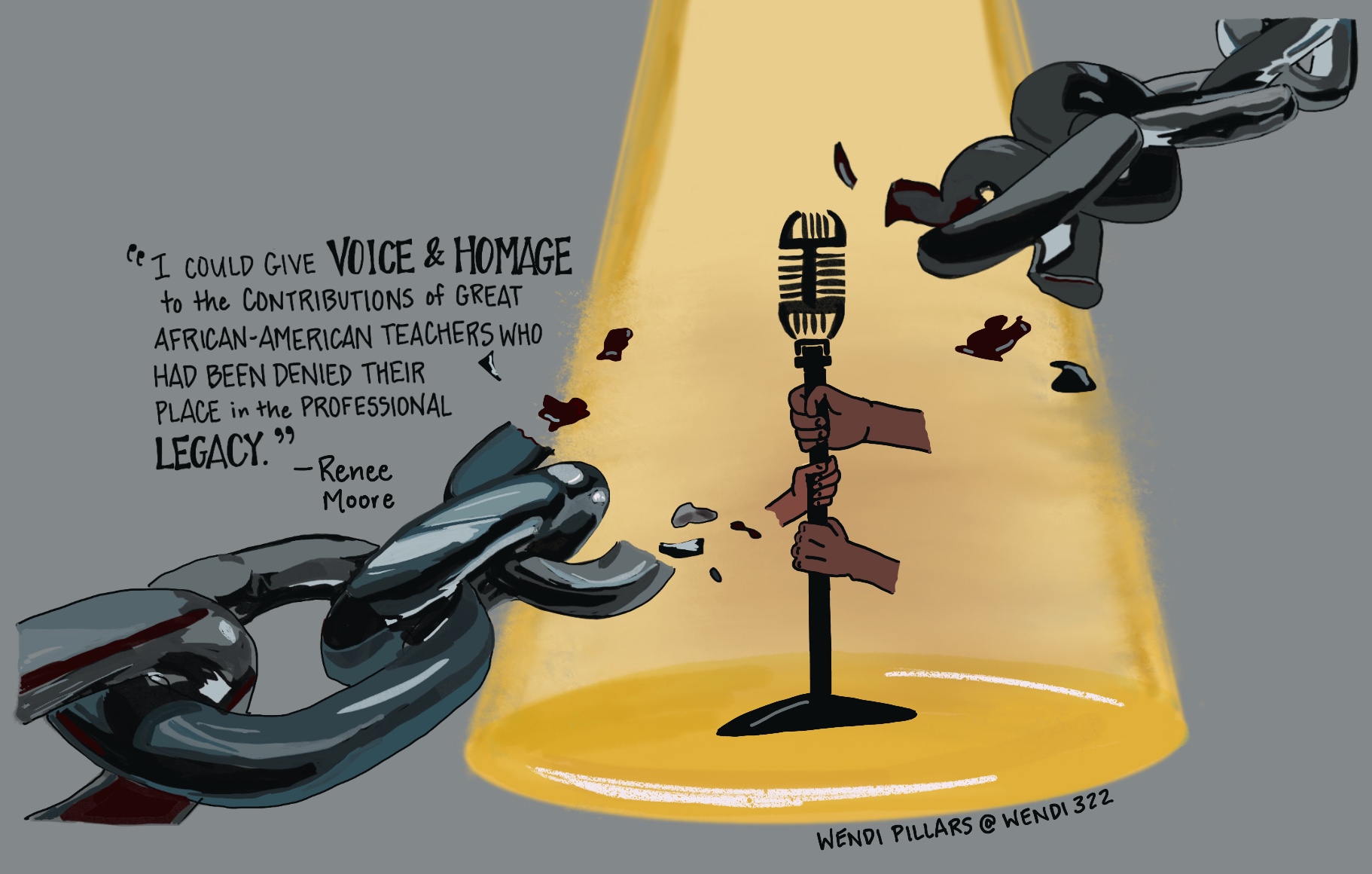

Network connections have paralleled my teaching career and propelled my growth as a teacher leader. About four years into teaching, as part of my graduate work through the Bread Loaf School of English, I helped pioneer the use of online exchanges to develop literacy skills among rural students via what was known then as the Bread Loaf Rural Teachers Network (BLRTN). Bread Loaf also introduced me to classroom action research, launching what would become a ten-year self-study about the teaching of Standard English to African American students. That research led to invitations to share at various venues. These opportunities mattered because there I could give voice and homage to the contributions of great African American teachers who had been denied their place in the professional legacy.

By the late 1990s, I was active in multiple teacher networks. One day I was invited to join the newly formed Teacher Leaders Network (TLN) sponsored by the Center for Teaching Quality, now Mira Education. Through TLN, I began my education blog, TeachMoore, and started working on Teacher Solution projects, tackling issues such as performance pay and teacher preparation. My participation in TLN and other networks also increased my opportunities to work with various groups addressing educational policy.

However, even years of professional accomplishments did not count when it came time to make the decisions that affected my own school and students. At one crucial juncture in my local school district, despite our students’ rising test scores, graduation rates, and college enrollment rates, the district hired a white consulting firm. The other teacher leaders and I were not just ignored but ordered to implement generic classroom practices from people unfamiliar with our students or our community. The high-quality, culturally-appropriate curriculum guides we had developed over two years (much of it on our own time) were discarded. The consultants were given the authority to monitor our classrooms and make sure we were teaching from the scripts they had given us. I share this cautionary tale because I’ve heard too many such stories from teacher leaders, especially from teachers of color, around the nation.

During this period, teacher networks were blooming, particularly on social media. Many were subject or location-specific, but most were true grassroot developments of teachers, particularly teacher leaders, trying to find each other and informally overlapping in membership and purpose. I think the growth was fueled by the joy of finding access to like-minded folk, or colleagues willing to share and listen.

I realized there were two significant differences between my highly accomplished African American teacher predecessors and me. Under the system of legal segregation, Black teachers (who were concentrated mostly in the South) had developed an extensive, sophisticated professional development network centered around the Black teacher associations (reverently referred to as “The Association.”) I had heard of this network and experienced its pedagogical products, but I entered the teaching profession after its dismemberment. The other difference between my highly accomplished mentors and me is that I have had access to venues and opportunities formerly closed to Black teachers, thanks primarily to their sacrifices and struggles. I vowed to use the platforms now opened to me to challenge the racist misperceptions of African American educators and our students.

A crucial step in that direction was the 2014-16 collaboration between Mira Education, the National Education Association (NEA), and the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) to develop a social justice curriculum that eventually became part of the NEA’s Teacher Leadership Institute (TLI). While helping to develop and teach that curriculum, I witnessed the powerful potential of uniting three teacher networks (of which I was part) around specific work that would directly impact student learning and create more equitable learning environments for potentially thousands of children.

Black educators’ work and voices are still blocked at many levels. I risked censure or worse for my research and teaching practices which unapologetically built on the work of distinguished Black educators and researchers. Yet, my limited work on national and state levels suggests that one Black teacher from the Mississippi Delta can have some impact on policy and teaching. Imagine what an engaged network of such teachers could accomplish for the profession, for students.

It is significant that many of the most vibrant teacher networks and movements of the past decade, such as EduColor, had at their core people who crossed paths via the Teacher Leader Network and Mira Education. The networking of networks not only amplifies the work of those who are already teacher leaders but the healthy (often challenging) cross-pollination helped produce more leaders and networks. Networking with other teacher leaders and helping to mentor new ones has also provided critical leverage against marginalization and isolation, especially for those of us in rural settings.

Teacher leadership still remains widely underutilized and unrewarded in most school systems. However, unlike when I started teaching, we now have a generation of educators who believe becoming highly accomplished teachers, and teacher leaders are normal career expectations. It is also assumed that teacher leaders should intentionally grow in cultural proficiency and develop as advocates of social justice within their schools. Due in part to the work of teacher networks over the past twenty years, other Black teachers and I are reclaiming our pedagogical heritage and re-asserting its value for broader educational policy and teacher preparation.

To paraphrase the song “I Remember, I Believe” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, I do remember the struggles and contributions of my pedagogical elders, and I believe their work prophetically points us to how the teaching profession should look.

Building Collective Leadership from the Central Office

Nader Twal is a program administrator for Innovative Professional Development (iPD) in Long Beach Unified School District. He is an accomplished teacher. In November 2003, his outstanding instruction was recognized by the Milken Family Foundation’s prestigious National Educator Award.

If your focus is on cultivating learning for each student even as student needs grow more diverse, then you know no one person has all the skills to accomplish that work. Collective leadership offers an approach that turns every staff member into a leader prepared to play a role in student support and success. In this interview, Long Beach USD program director Nader Twal explores the role that district central office staff play in accelerating collective leadership in each building.

How do you define collective leadership as a leader in the central office?

Collective leadership represents the recognition that we can operate in one of two ways: as a human-centered enterprise or as a sterile system. Systems can be very mechanical; they have interchangeable cogs. But education is a human-centered enterprise. We cultivate the minds, hearts, and emotional well-being of students and staff. Human-centered efforts focus on people, so the system operates more like an organism and less like a machine.

The analogy I would use is an amoeba under a microscope. Think about the amplified image of a needle poking the amoeba and the entire thing moves. It is so interdependent that touching one part has a ripple effect across the whole.

Collective leadership can be represented in that way. There is recognition that no one person has all the knowledge, talent, skills, and experience to meet the needs of everyone in the system. You need to have collective leadership to be highly effective. If you’re about cultivating success of all kids, then you have to recognize that it is impossible to do it alone.

No one person has all the knowledge, skills, and experience to meet the needs of everyone in the system. That’s why collective leaderhsip is important.

Collective leadership is the recognition of varied sets of skills and strengths that need to be called out and called up to operate as an organism rather than merely as a system. Collective leadership amplifies natural strengths while modeling and developing potential areas of strength.

What is the power of collective leadership in both shaping the culture of a school and improving student learning?

The power of collective leadership to improve student learning depends on whether that collective leadership is a structure or a value.

We can build collective leadership structures that have no impact. The small schools movement, a powerful catalyst for positive change when implemented well, is an example. Many wanted to personalize education by shrinking schools, but we didn’t see an impact for students because everything stayed the same—only in smaller learning environments. Personalization isn’t about the size of a school, it’s about people knowing your name and teachers coordinating efforts for students. Changing the structure should have changed the way schools were doing business, but instead some kept doing things the same way they always had, just in smaller spaces.

Shared governance and distributed leadership are amazing ideas, but they have to be applied appropriately to carry meaning. For many, those terms mean representation in a meeting, but that isn’t voice, nor is it impact. Empowerment for teachers at the site level is expressed in how collective leadership functions. What are the norms that govern group dynamics? How are decisions made and implemented? Is there allowance for failure?

How does collective leadership move from an idea on paper to transforming outcomes for students?

There has to be a shared vision and purpose that everyone finds value in. There has to be adequate time given for people to build relationships within the group — professional relationships, not ropes courses. I’m talking about creating an atmosphere where real discussion can happen and people are creating meaning together, which is a messy process. Collectively making meaning creates culture, which becomes self-sustaining.

There has to be real decision-making power in that collective. Organizations that value collective leadership are flat—with few or no levels of middle management between staff and executives—when priorities are being decided, but they become vertical—with managers and supervisors responsible for divisions of labor—when it comes to execution.

As a district administrator, I won’t be the implementer once a decision has been reached. I will resource, strategize, and enable implementation, but I won’t be leading it with the kids. Our principals, teachers, and support staff do that, so their stake in the work has to be honored. All voices matter to arrive at a decision, then it has to be flipped vertically to execute it.

What is the relationship between individual leadership and collective leadership?

Collective leadership, if it works well, builds up individual leadership capacity. Conversely, individual leadership capacity functions and thrives best in collective leadership environments where it has a context to have an impact.

There’s a whole psychology about the difference between power and influence. Power is positional. I can get you to do stuff. I can build up the resume and titles to give orders, which builds culture of compliance. But when I leave the school or district, so too does everything I prioritized.

But the psychology of influence is that my individual leadership gets valued as part of the collective. My voice now matters in informing the collective. It is shaping not just work we do, but the thinking and approach to the work. In this case, if I were to leave, my influence is sustained. Leading with a greater skill set and a deeper body of experience that I can bring to different contexts.

Individual and collective leadership only detract from one another when they conflict. They only conflict when used as a mechanism of compliance rather than change.

True leadership isn’t threatened by the leadership of others. Every leader should want to bring his/her best to a team.

If you’re an individual leader invested in collective whole, you are bringing your best to a great team. You also know when to let others shine because they aren’t a threat to you, they are an asset.

How can teachers and administrators support and encourage collective leadership?

There are three layers that come to mind. First, there has to be structural commitment to collective leadership. Symbolism in the representation, time devoted to meaningful conversations, and some value attached to it in terms of how it is resourced and empowered to make decisions. To show it is valuable, you have to create time for people to meet, and fund the work tied to what they are doing, and give them real say in what happens.

The second layer is about support, coaching, and training. How does one function in these groups? How do they come to consensus and reach a decision? People need to have a framework for getting the work done.

The third layer is establishing how the group’s deliberations and conclusions are communicated to the rest of the staff. How does the rest of the staff access and inform what is happening in that group? It is not just a matter of describing what transpired in a meeting, nor is it sharing an agenda of the five things that should be covered in the meeting. Appropriate communication recognizes that in collective leadership contexts, real decisions are made. For those to be informed and implemented, people have to trust that they are heard. And people have to trust that when a decision is made—whether or not they agree with it—that it was adequately addressed. That kind of trust is built over time with early wins and small successes.

When people are moving into collective leadership from more traditional models, I think ‘high process and low content’ works best to get people used to functioning in that environment. When they are comfortable functioning in that new space, they have internalized the work and the system of the school has shifted to function more like an organism.