Alesha Daughtrey

Doing More With Less: Preparing for the ESSER Funding Cliff

Next fall’s $190 billion federal funding cliff may be causing almost as many sleepless nights as the pandemic did. For superintendents and other K12 district leaders, early Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds were essential for one-time emergency spending. Later, districts spent more to address learning loss, staffing needs, and other capacity-building to support full recovery.

Assessments of learning loss and equity implications for communities suggest that full recovery from the pandemic is far from finished, even if ESSER funding is ending. It’s easy to build an argument that schools need more base funding to continue to hire and retain educators, restore long-vacant positions for counseling and other student supports, and provide intensive programs for targeted students.

But the reality is that districts and states will have to identify cuts with the end of ESSER funding. The sooner and more thoughtfully districts can begin planning, the better. Budget cuts are unavoidable, but district leadership teams can use this as an opportunity to focus on what is actually important. Four practices can make sure that the cliff doesn’t send you into a free-fall.

Take time to articulate priorities.

From paraprofessionals to the superintendent’s office, educators across all roles agree on one thing: they never have enough money or time. While it’s hard to make more of either, we can choose how we spend both. That means getting distinct about what is most important – not just what’s ideal or urgent – and putting all our energy and resources behind just those things.

The daily urgencies of our work can make it challenging to take the time to identify these top priorities, let alone articulate them for school communities. But it’s an essential first step. If we don’t know our priorities, we can’t protect them — and that means cuts will be felt even more deeply.

De-silo the decision-making process.

Defining “priorities” depends on your perspective. Meeting the needs of 30 individual students and determining what works at the district scale are and should be entirely different viewpoints for decision-making, even when they both seek to center learners’ needs. When those viewpoints aren’t reconciled, leadership teams tend to rely on a combination of mandates, roll-outs, and seeking buy-in to encourage alignment with tough calls.

While leadership requires those tough calls, it need not require tough talk.

The harder the decisions are — and cuts of this type will be very hard — the more important it is to communicate about priorities with others and not just to them.

In over a decade of helping school and district teams tackle challenging changes, our organization has never seen a single “roll-out” of an important decision work smoothly based on an announcement. Rather, it requires consistent and connected communication that links back to the priorities you’ve already discussed together.

The time spent to share ideas, ask questions, and seek input is significant, but it is much less time — and much less stressful time — than the time that leadership teams otherwise need to spend in contentious bargaining tables, staff meetings, public hearings, and press conferences.

Fight the epidemic of “program-itis.”

Even evidence-based programs with robust support from skilled educators can fall short of their promise for students and schools. And that can sometimes be the best-case scenario. Many, if not most, of the programs that districts and schools plan to implement, require extensive (and expensive) training for staff before they can get off the ground or demand total fidelity to work as promised.

Sometimes there are just too many programs to be done well. In one improvement leadership network we have supported, school leadership teams identified more than 30 programs adopted in relatively small elementary schools. When staff are struggling just to name all the programs they have in place, it’s a good bet that they are struggling to run them.

Programs should support students and educators – not the other way around. Budget cuts not only offer us the opportunity to trim away what’s not aligned with priorities and getting results, but also to think about what is really sustainable. No matter how much money you have to spend on potentially effective and helpful programs, too many of them create a deficit of time and energy that contributes to stress, burnout, and attrition while doing little for student learning.

Plan proactively.

K12 education continues to be asked to do more with less. The repercussions of cutbacks are real, as is the stress that these decisions place on district leadership teams and personnel. But we can buffer those impacts if we shift from a focus on scarcity, which engenders feelings of restriction and dread, and replace it with a planned focus on opportunities to shed that programmatic “clutter” in ways that help us serve students better in the long run.

Our book, Small Shifts, Meaningful Change, offers a protocol in Chapter 4 to help you bring all these ideas together to reimagine your resources as part of a single 90-minute meeting. You can find more free tools and discussion guides on Mira Education’s website or contact our team for advice and support.

Building Sustainable Leadership Practices

When I’m not working, I’m often running — for exercise or after a young child – and I’ve had my share of injuries, including a pulled hamstring that wouldn’t heal. When I complained to the doctor, she shook her head at me.

“Look,” she said, “the hamstring is actually a bundle of muscles. The way you’re moving yourself forward is using some of them more than others. Until you’ve got them all engaged equally, you’ll be hurting. And you won’t be running — at least not as fast as you want to.”

Running the change leadership race

Aches and pains in moving forward — and struggles to move forward at all — are an everyday challenge for education professionals and for some of the same reasons. No matter the role, we’re charged with moving others from point A to point B. We change how students engage with content and master the work of learning, how fellow practitioners guide young and professional learners, and how fellow leaders exercise sound judgment.

Put another way, moving change forward is our work.

But that doesn’t make it easy. Whether it’s greater emerging needs among student enrollment, staffing shortages and budget cuts that ask public schools to do more with less, new faces on a team, or rapid shifts in standards and other mandates, it all adds up to nearly constant pressure for educators to make complex shifts in how they do every aspect of their work.

Fatiguing the muscles of leadership

The pace of these changes can be difficult to manage and sustain — sort of like trying to run a half marathon on a hurt leg. In fact, 70 percent of change efforts fail due to isolation from a supportive team, conflicting priorities, confusion about why change is happening or what it looks like, and a lack of individual or collective efficacy in navigating the change.

Schools and districts often tend to resort to single solutions and single leaders to turn things around. The idea is that pushing on the same programs and people will accelerate progress toward a goal even though the change failure rate and the rising frustration levels among teachers and administrators show us we’re wrong.

Pressing on the same “muscles” to power change over and over again while others atrophy is a recipe for slowdown or worse. And it’s not as if we have a shortage of options. With one in every four teachers ready to take on school-wide leadership work alongside teaching, schools and school systems have lots of leadership “muscles” they can engage. We know collective efficacy is a key to instructional improvement, and research shows that engaging educators in collective leadership is the key to sustaining transformational change in schools.

Moving forward together

So where do we start? At Mira Education, we find that the educators and leaders who are successful make three big shifts to retrain those leadership “muscles” so they work better together:

- From leaders to leadership.

Traditionally, leadership development has been about developing individual leaders, usually administrators. Given high rates of turnover in these positions, it’s difficult to see the path to ROI or sustainability in that approach. In fact, three-quarters of all principals agree their work is too complex to be done by a single individual anyway. Stone Creek Elementary and others with which Mira Education has worked think about how they develop larger and more robust teams to share the leadership load. That way, if one leader leaves, change doesn’t lose its momentum because every leader creates more leaders. - From compliance culture to rethinking resources.

Every school and district lives with mandates to implement programs, manage budgets, and fill Full Time Equivalencies (FTEs), each of which can feel siloed at best and incoherent at worst. Good leadership manages them well, but great leadership figures out how to reorganize them into a coherent whole. Led by a team of administrators and teachers, Walker-Gamble Elementary did just that. Today, every teacher at Walker-Gamble has at least five hours of weekly learning and collaboration time, staff report increased collective efficacy, and students are meeting both their own learning goals and state standards. - From siloed to networked.

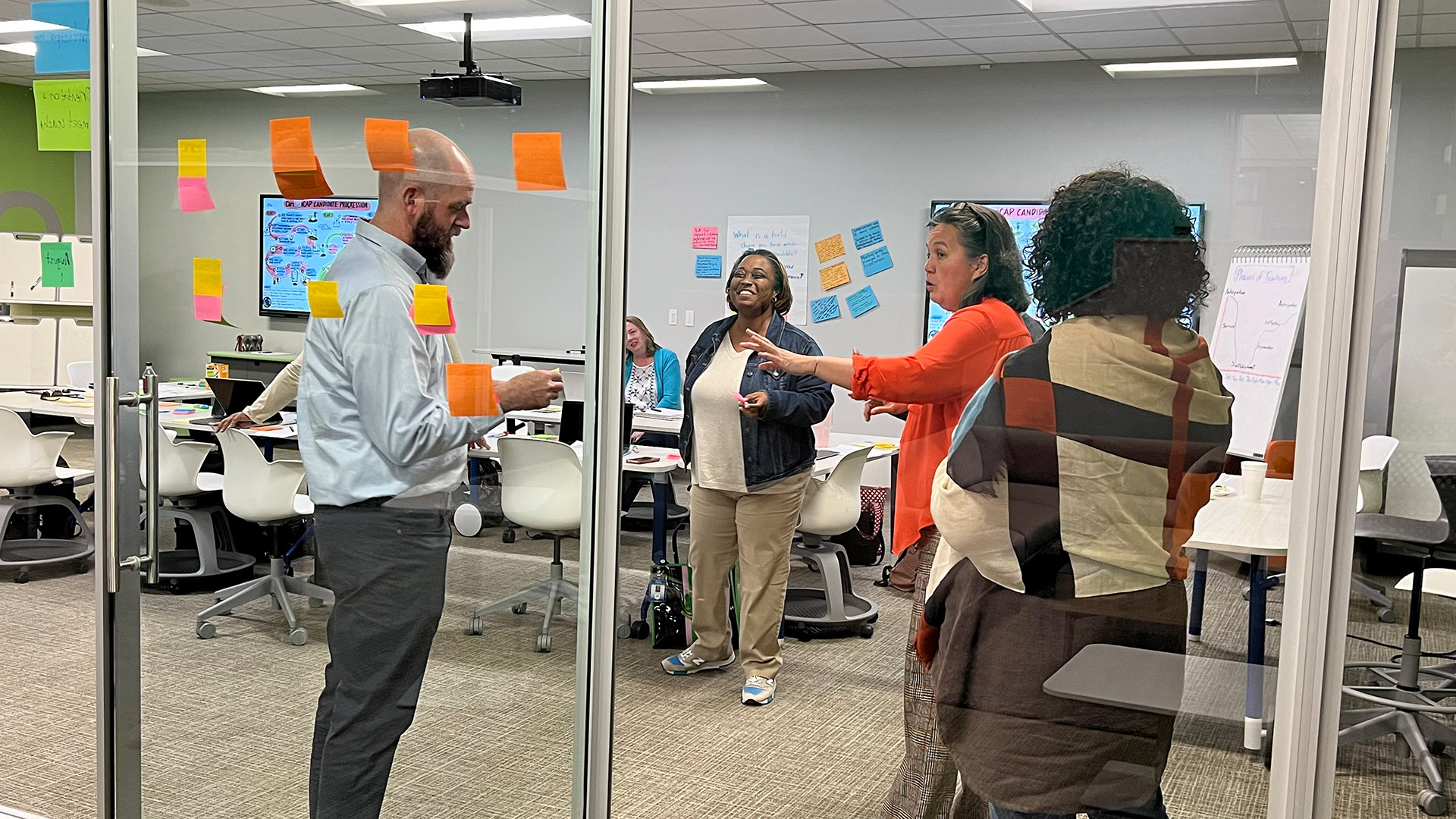

These schools didn’t learn how to build this kind of capacity or get this kind of results on their own. They learned from one another. Teachers and administrators from each school’s leadership team visited partner schools as part of a network hosted by Mira Education. Likewise, we partnered with Northwest Independent School District (ISD) to help them find more effective ways for schools to set goals aligned with the district strategic plan and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) goals, break down barriers to collaboration among schools, and engage more of their staff in ongoing innovation and improvement efforts.

We know through these partnerships and others that collective leadership works where traditional improvement programs have not. And we know that teachers and administrators are equally important in putting practices in place to create sustainable educator leadership pipelines that have been challenging to build in other ways. But we also know that it takes many, many more stories of those successes to make a movement. Otherwise, we’re working with lone runners instead of a real race.

What is your school or district doing to build the power of teachers and administrators to lead collectively? Find tools and insights to power your work on our website, and share what works with us via social media using the #collectiveleadership hashtag.