Blog

A Better Way to Finish Strong

How Collective Leadership Helps School Leaders Finish Strong

The month of May is a marathon, not a sprint. Testing, hiring, celebrations, and next-year planning. It’s all happening at once, and the pressure to “finish strong” is real.

But for too many leaders, “finishing strong” gets translated into “doing more,” and often doing so alone.

There’s another way.

What Collective Leadership Looks Like at the End of the Year

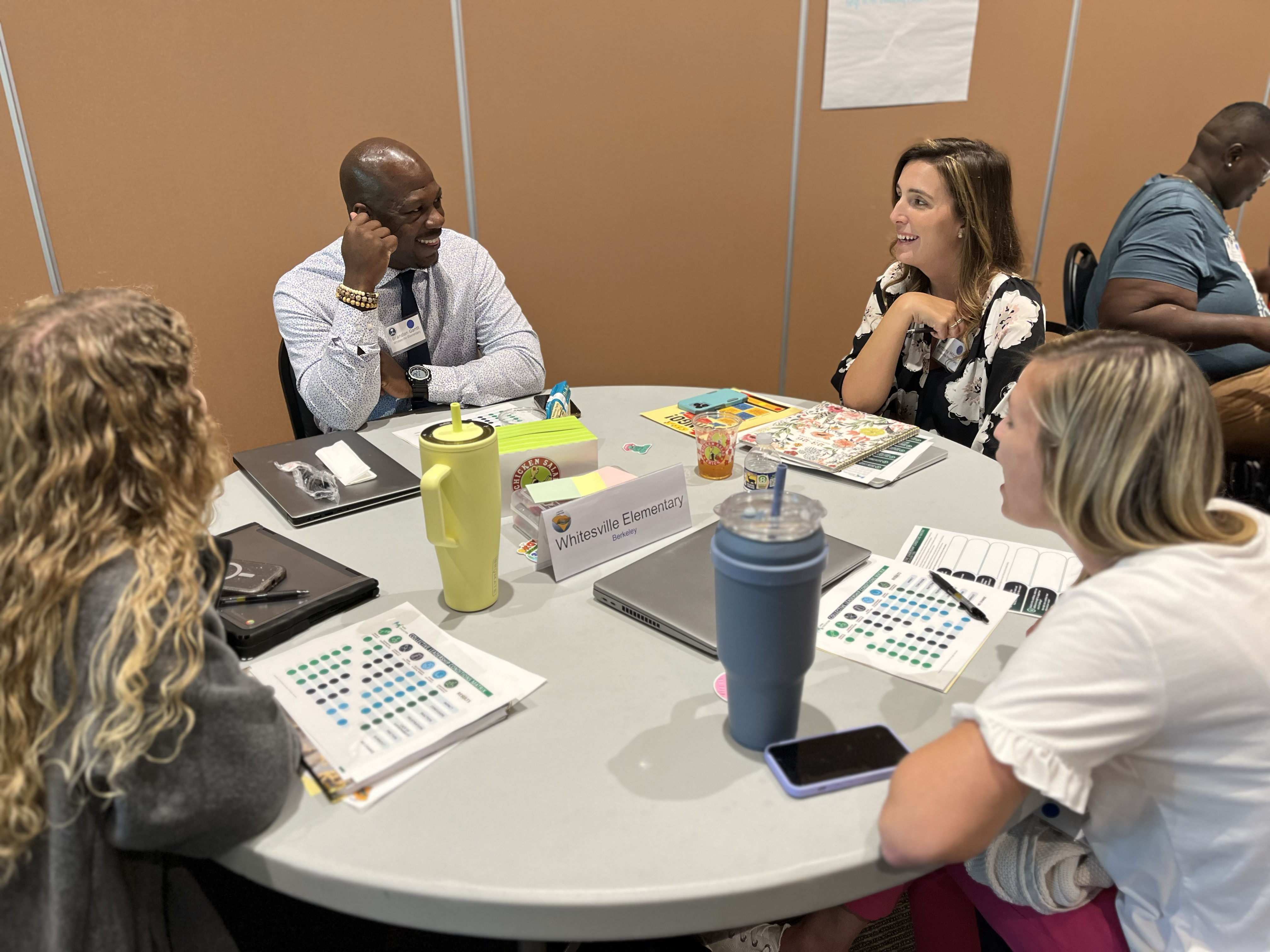

The work may not be easier, but leaders in these schools and districts aren’t just surviving the end of the year. Rather, they’re designing it with their teams to co-own the work and the results. Here’s what that looks like in practice:

Desiloed Decision-Making

Instead of tackling hiring, planning, and budgeting in parallel conversations, they bring the work into one shared frame. In our work with the University of Maryland School Improvement Leadership Academy, principals and assistant principals focus on competency-based professional learning to sharpen their skills in inclusive leadership practice.

“SILA provided research with practical skills to improve school systems. With the skills I developed in SILA, we were able to increase our attendance rate this year from 70.1% to 83.1%.” Allison Johnson, J.D., NBCT, Assistant Principal, Anne Arundel County Public Schools

Distributed Reflection

Every team, not just administrators or the central office, has space to look back, name what worked, and surface what needs attention.

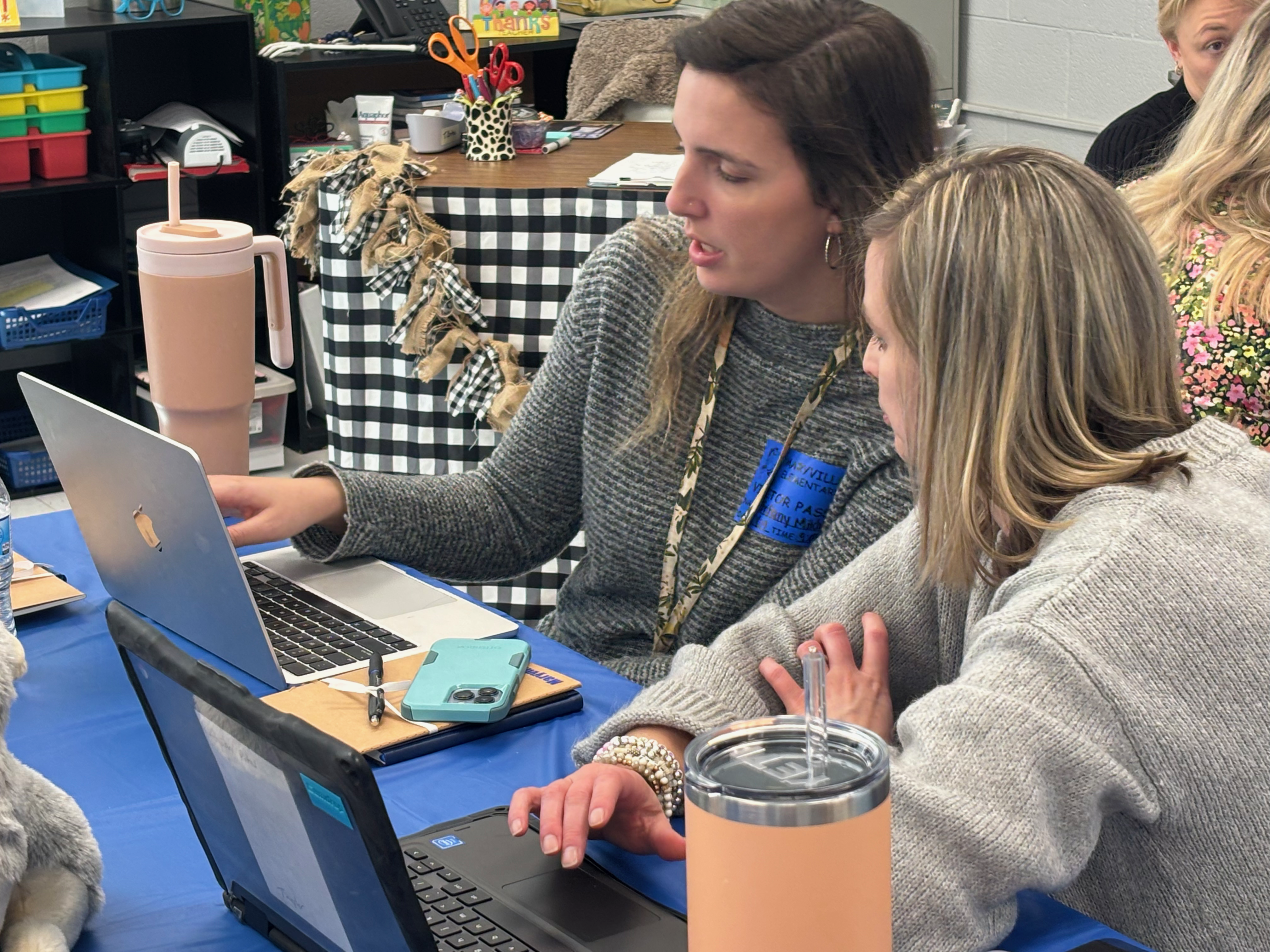

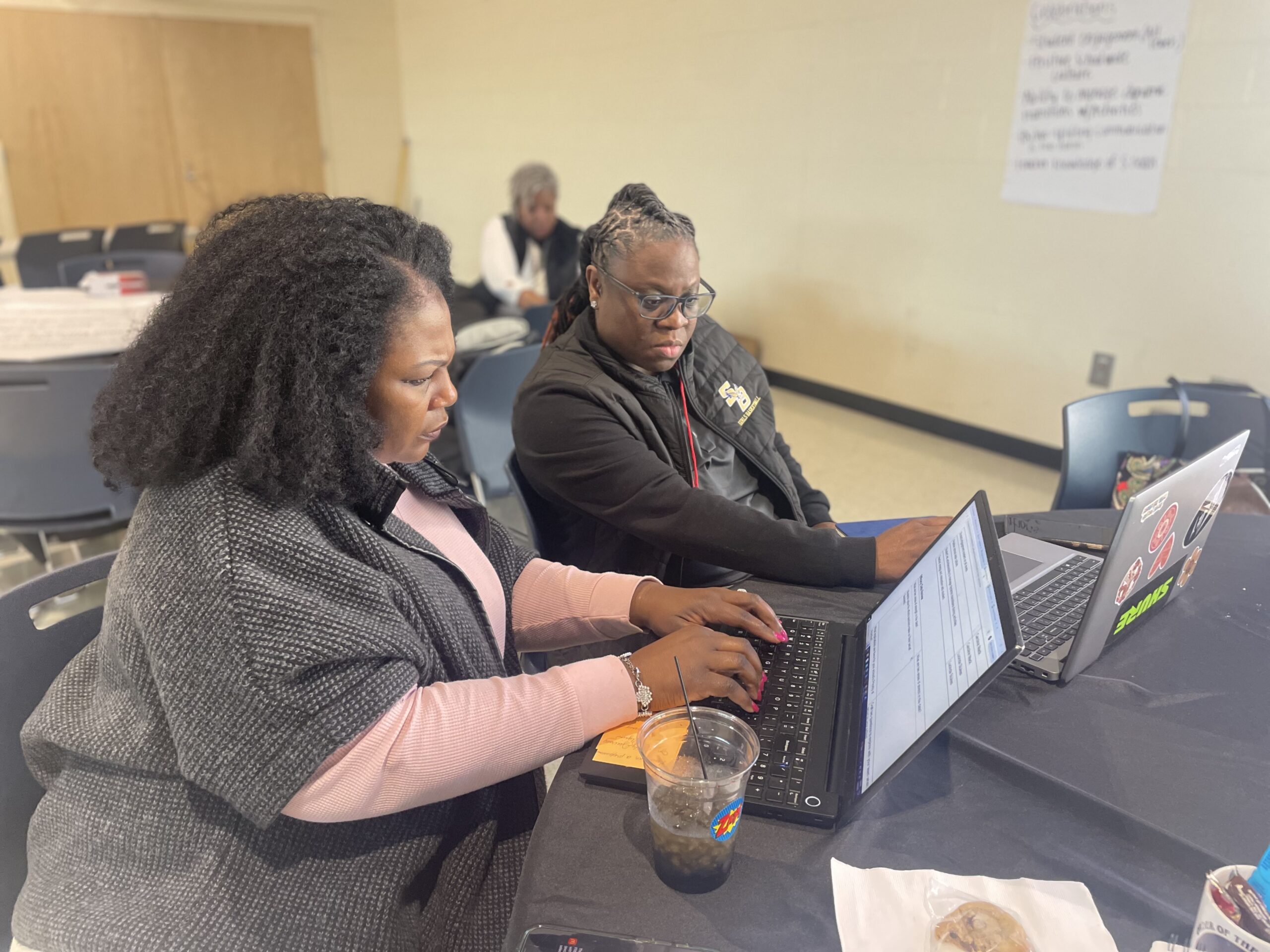

As part of our partnership with the South Carolina Department of Education, 31 schools across 15 districts are implementing collective leadership practices to spur improvement and reflect on what their schools need to be a thriving learning community.

Centered co-ownership

When the temptation to “just get it done” kicks in, they ask: Who else could lead this? And more importantly, who is already leading, but hasn’t been named?

By coming together to view student data as a team, Scott’s Branch Middle School was able to share to increase its capacity to support each student.

“Student achievement was always the core of our work. But the problem was we were all on our own islands. …Doing the data walls helped us see a clear picture of what each child needed.”—Caroline Mack, Teacher of the Year, Scott’s Branch Middle High School

When leaders aren’t carrying the load alone, they’re part of a system that holds together, even in the toughest weeks.

Try this

End-of-year pressure can make us default to “just get it done.” But co-leadership requires us to slow down and shift the approach. Try this:

- Map out a key end-of-year task that’s currently sitting on your plate. It could be anything from finalizing budgets to planning PD or preparing graduation events.

- Identify two other team members already contributing to this task, whether actively or behind the scenes.

- Name one action you can take to share the ownership of this task with them publicly: acknowledging their role in a meeting, shifting responsibility, or asking for their input on key decisions.

The goal isn’t just to share the workload. The goal is to co-own the process and outcomes as a team.

Learn more about how schools are implementing collective leadership to drive real change.

Uncertainty ≠ Instability: 4 Key Strategies for Education Leaders to Support Staff Through Change

Change in education is constant, but uncertainty doesn’t have to lead to instability or getting stuck. Education leaders play a crucial role in navigating the unpredictable nature of school improvement, curriculum shifts, and policy changes. By focusing on what’s within your control and supporting your staff through the unknown, you can lead confidently, reduce stress, and promote a healthy, collaborative school culture.

Here are four actionable strategies to help education leaders support their teams during uncertain times and create stability in change.

1. Focus on What You Can Control: Leadership Strategies for Success

In uncertain times, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by factors beyond your control, like changes in education policy, fluctuating budgets, or evolving state mandates. However, focusing on what you can control is the most effective way to maintain stability within your team.

You can’t control everything, but you can control your leadership approach: how you communicate, how you advocate for resources, and how you support your staff. By focusing on these areas, you can avoid burnout and build a positive, proactive school culture.

Key Takeaway:

In times of uncertainty, education leaders should focus on the leadership actions and decisions within their control. If it is not yours to do, it is not yours to worry about. This maximizes the impact you can have and fosters resilience.

2. Communicate Early and Often: Building Trust with Transparent Leadership

Effective communication is one of an education leader’s most important tools during change. Proactive communication ensures that staff members are informed, reducing confusion and anxiety about potential shifts.

Whether it’s about curriculum updates, policy changes, or school-wide initiatives, keep your team in the loop early and often. By being transparent and consistent, you prevent assumptions and encourage a culture of trust. Staff should know they can rely on you for updates and information.

Key Takeaway:

Communication is the foundation of trust. Early and frequent updates are key to keeping staff informed and reducing uncertainty during periods of change.

3. Avoid Siloed Decision-Making: Promoting Collaboration Across Teams

Siloed decision-making can lead to misalignment and frustration, especially when facing uncertain times. When teams or leaders work in isolation, it often results in confusion and resistance to change. Instead, promote collaboration across teams and departments to ensure alignment and foster a shared sense of ownership.

Involve staff in decision-making processes early on and create open channels for feedback and collaboration. This ensures decisions are made with collective input, which boosts morale and reduces the risk of misunderstandings.

Key Takeaway:

Collaboration is essential for navigating uncertainty. Break down silos by ensuring decisions are made with input from all stakeholders, aligning your efforts across teams and departments.

4. Make Small Shifts for Meaningful Improvement: Sustainable School Change

Instead of waiting for large-scale changes, focus on small, incremental shifts that will drive long-term improvement. In times of uncertainty, making steady, manageable changes is more sustainable and less disruptive.

Rather than overhauling systems or processes, make consistent adjustments that can be refined over time. Whether revising a program, testing a new strategy, or making small tweaks to daily operations, these incremental changes lead to sustainable growth.

Key Takeaway:

Sustainable change comes from small, intentional shifts. Focus on incremental improvements rather than major disruptions for more significant long-term impact.

Looking for More Resources?

Leading during uncertain times doesn’t have to be overwhelming. By focusing on what you can control, communicating effectively, promoting collaboration, and making incremental improvements, you can guide your staff through unpredictable changes confidently and clearly.

For more tools and resources on leading through school change and supporting your team during uncertainty, visit www.miraeducation.org. Our free resources can help you lead for sustainable change and build a stronger, more resilient school culture.

Removing Barriers to Impact: How Education Leaders Can Find Focus in the Chaos

Why Education Leaders Get Stuck

Education leadership is filled with competing priorities — curriculum implementation, teacher retention, student success, and operational challenges. With so much happening at once, even the best plans can stall.

Maybe a new initiative isn’t gaining traction. Maybe a curriculum shift hasn’t delivered the expected student growth. Or maybe, despite endless meetings, the same challenges persist year after year.

When this happens, it’s often not because the ideas are wrong — it’s because barriers, like follow-through, misalignment, and outside factors, prevent real progress.

The solution? Removing barriers to impact — focusing on what truly matters and clearing the path for meaningful change.

How to Remove Barriers and Gain Momentum

As a design and implementation partner, we’ve helped school and district leaders refine their vision and strategy to meet their unique needs. The key? Harnessing collective leadership, aligning expertise with goals, and identifying what’s standing in the way of progress.

Here are three powerful ways education leaders can remove barriers, focus their efforts, and drive sustainable impact:

1. Leverage Expertise: Leadership is a Team Sport

The best school and district leaders don’t try to do it all alone. Collective leadership ensures that the right people are making decisions in their areas of expertise. When teams collaborate effectively, they remove roadblocks that slow down progress.

Action Step: Identify key strengths within your team. Who can take the lead in specific areas? How can you build leadership capacity across your school or district?

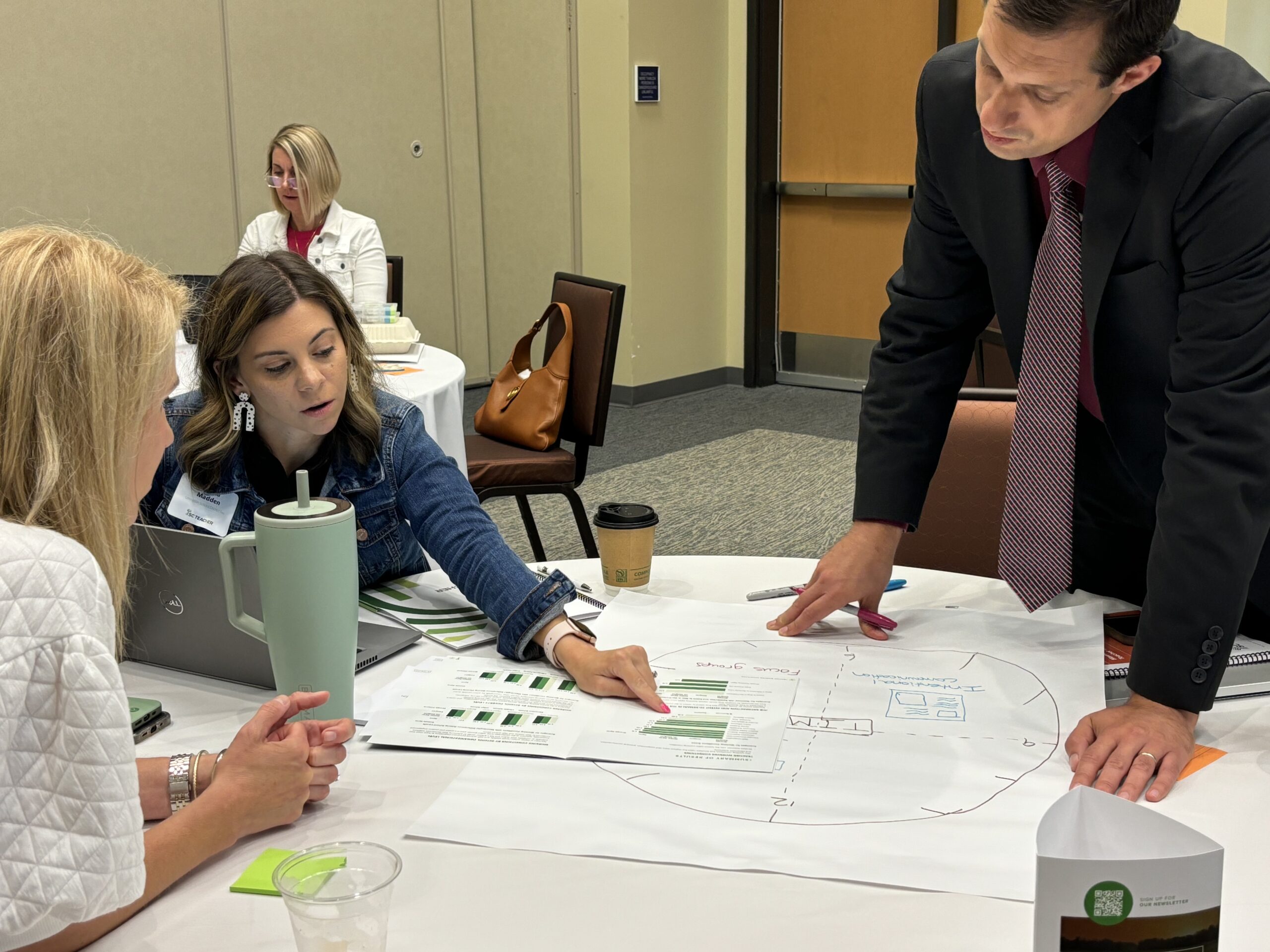

2. Step Back & Reflect: Use Data to Identify Roadblocks

Great education leaders don’t just collect data — they use it to pinpoint barriers and adjust strategies. Reflection isn’t just about checking progress; it’s about identifying what’s holding your team back.

Action Step: Schedule a data-driven reflection session with your team. Use both qualitative and quantitative data to assess progress, celebrate small wins, and adjust your school improvement plan accordingly. Download this tool to guide your session.

3. Turn Reflection into Action: Remove What No Longer Works

Reflection without action leads to frustration. The most effective education leaders take insights and turn them into concrete next steps—especially when it means eliminating outdated practices.

Action Step: After every strategy session, define one priority, assign ownership, and set a clear timeline for action. Removing unnecessary tasks and refining focus helps teams gain momentum. Download this tool to help you sort through initiatives and tasks to refine or remove.

Removing Barriers to Impact: A Mindset Shift for Education Leaders

Progress doesn’t come from doing more — it comes from focusing on what truly moves the needle. By stepping back, leveraging your team, and committing to actionable school leadership strategies, you can clear obstacles and create lasting change.

Feeling stuck? Let’s remove the barriers to impact together. Connect with Mira Education to build momentum and implement high-impact, sustainable school improvement solutions.

The Power of School Learning Labs

Observing Collective Leadership in Practice

How do schools make meaningful, sustainable change?

It’s a question educators ask themselves every school year.

In our work with partners, we’ve learned that big, innovative ideas do not always shake up a system. It’s the small shifts in practice that lead to sustainable school improvement.

Over the last seven years, Mira Education has partnered with the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE) to support schools in making small shifts for significant impact through a collective leadership approach.

Collective leadership is a research-based approach that harnesses the expertise of each team member to multiply leadership capacity and bring more perspectives into the decision-making process.

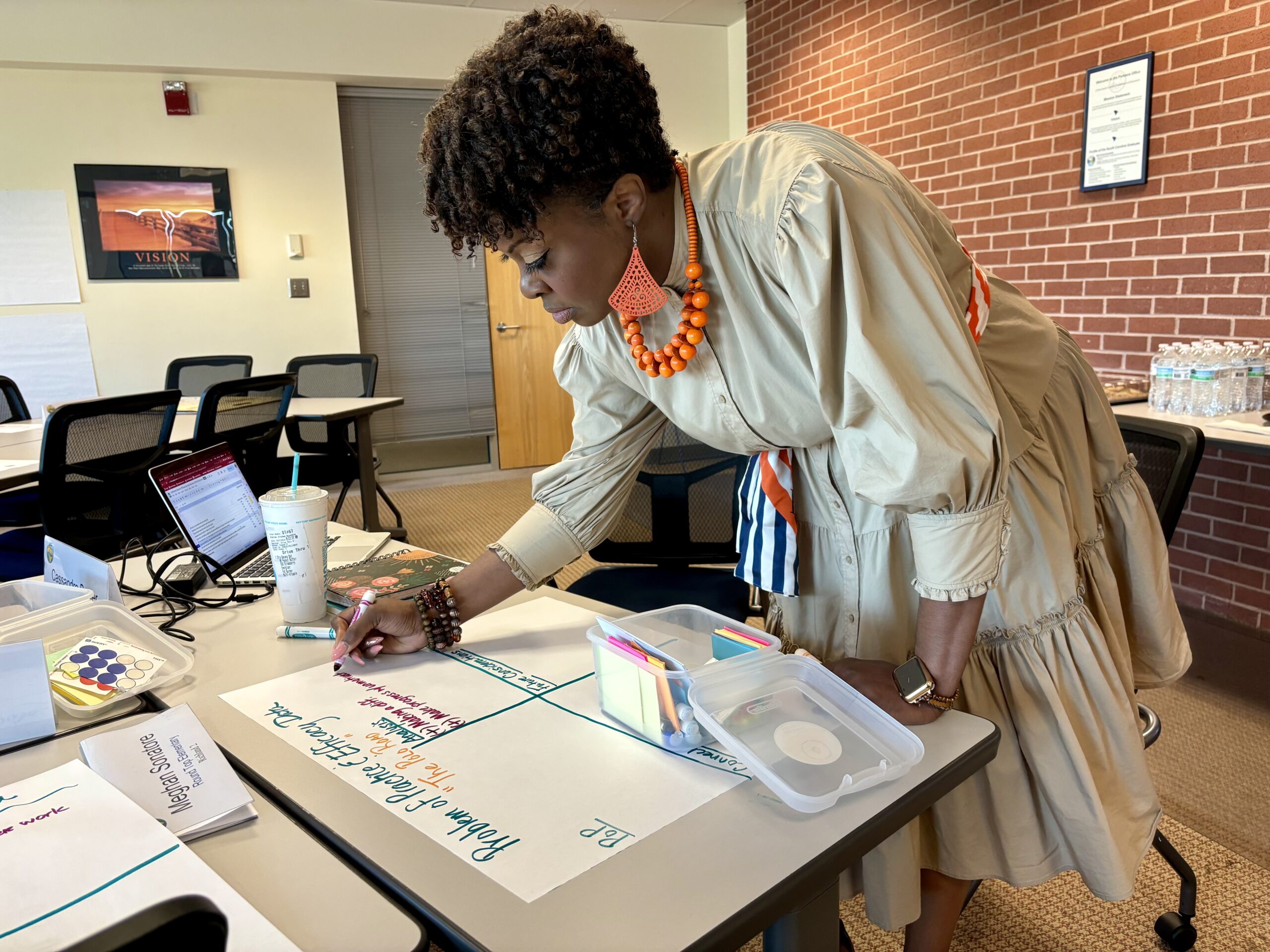

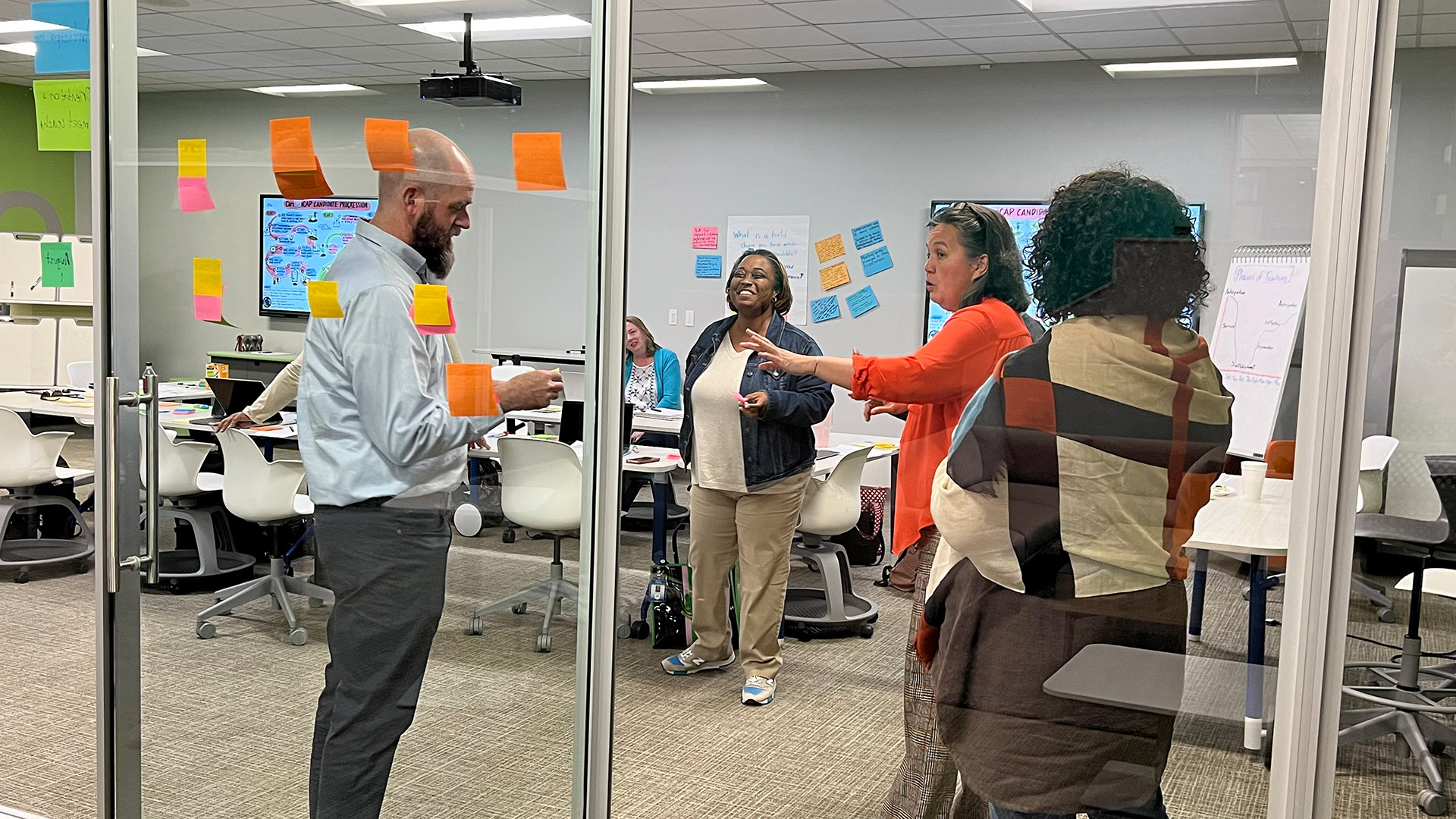

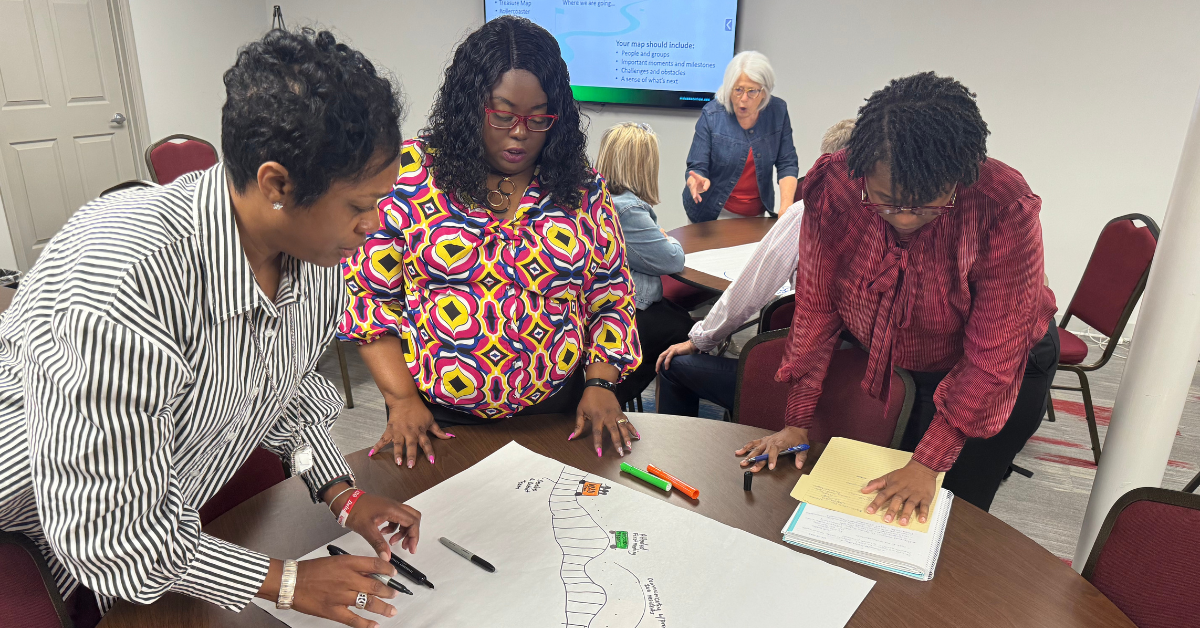

Collective Leadership Initiative

The Collective Leadership Initiative (CLI) was established in 2018, and 64 schools have participated in this partnership between Mira Education and the SCDE. As part of CLI, school teams across South Carolina come together to identify a Priority of Practice (PoP) for their schools. The PoP is a growth area for school teams will focus on for two years. Teams identify the actions needed to address their PoP and plan for small, sustainable shifts in their collective practice. To ensure there are a variety of perspectives and expertise at the table, CLI teams are comprised of educators across roles – administrators, teachers, and support staff.

But what does collective leadership look like in practice?

Learning Labs

To support teams in answering this question and to offer inspiration for shared work, CLI schools participate in learning labs. Learning labs are school visits to other CLI schools to obserce the impact of collective leadership in classrooms in real time.

Recently, Mira Education and SCDE co-facilitated four learning labs at Blythewood High School, Horse Creek Academy, J.C. Lynch Elementary School, and Maryville Elementary School. While each host campus had its own style, all participants observed classrooms, heard from staff and students, and asked questions about the host campus’ collective leadership practice.

Additionally, each school team examined its efficacy survey data. The efficacy survey is an anonymous survey administered by CLI that measures the degree to which teachers believe they impact one another and student learning.

This data-reflection is part of the CLI planning process. Schools will come together again later this month to adjust their approach and identify potential shifts to their PoP to better support their team.

Learning labs effectively allow educators to see collective leadership in practice. They help the theoretical approaches learned in CLI become tangible and, more importantly, actionable.

For support identifying a Priority of Practice and to learn more about applying a collective leadership lens to your work, email info@miraeducation.org.

Releasing Jargon for Innovation: Reframing the Language of Improvement

In my fourth year in education, our superintendent championed the word lagniappe as our staff mantra. At district-wide meetings, in e-blasts, and in all staff communication, he would remind us to embrace lagniappe as part of our daily routines. The word was deeply personal to him and, in turn, was meant to inspire staff to go the extra mile.

Lanyards and stickers were given on professional development days, and lagniappe was plastered on social media. It was the mindset we were meant to embrace as part of our staff identity. But, like several others, I had no idea what it meant or how to pronounce it. Many of us wore lagniappe on our school badges because it was a fun phrase, but we had no clue about what we were trying to embody.

I have since learned that lagniappe, pronounced lawn-yop, is a Cajun-French word meaning a little extra on purpose. This beautiful sentiment was completely lost on me while working in the district.

Identify Jargon

Although an atypical phrase in most of the K12 space, lagniappe is not unlike other education jargon. Too often, we use buzzwords and professional-speak to describe school improvement work without pausing to understand what those words mean in practice.

Moreover, school improvement can be overburdened by negativity just by the words chosen to describe the process and outcomes. Words like “compliance” and “mandate” can muddy the purpose of the work, leading to confusion rather than innovation.

How can teams overcome this confusion?

Start by naming and defining the words that impede collaboration.

Build a Glossary of Shared Language

Through discussion, invite team members to share words and phrases that reinforce compliance and accountability mindsets for them. Maybe it’s something as unique as lagniappe or as common as fidelity. Whatever the case may be, use your list to gain insight into how shared language shapes shared work.

As your team identifies terms, note why these words may not align with innovation and what words could be used instead. Use these prompts to guide your thinking:

- What mindset might this word or phrase evoke?

- How might that work against the innovation mindset we want to create across our team?

- What’s the word or phrase that would evoke an innovation mindset that could be used in place of the original?

Commit to Shifts

As you assess your shared language, be intentional in your follow-through and commit to reframing your shared words. Use these three prompts to help implement your new glossary and sustain these new shifts:

- What are some upcoming opportunities to practice these shifts in language?

- What will you and your team do to reinforce the use of words that support your innovation mindset?

- Determine a time to revisit the glossary you’ve created.

Download our tool, Reframing The Language of Improvement, for a complete facilitation guide and glossary template.

Onboarding with Intention: 3 Shifts to Improve the Process

The start of the school year is filled with energy, optimism, and intention-setting for everyone, and especially for new staff who will teach and lead alongside us this fall. The excitement and rush of a new year are terrific moments to engage new staff positively, but can also create special challenges for focused support that have to be addressed if we want to retain as well as onboard these colleagues.

As you prepare for new staff members, three mindset shifts can give the onboarding process fresh intentionality and purpose.

Onboarding Goes Beyond Orientation

Effective onboarding is an ongoing process that takes place over an extended period of time. Though onboarding can include aspects of orientation and training, it goes well beyond that.

Onboarding is defined as the action or process of integrating a new employee into an organization. In these times of teacher shortages and retention challenges, it is crucial that onboarding not only prepares new staff for work success but also creates a sense of belonging which can improve retention.

Consider the following questions as you design onboarding to actively engage new staff in the daily practices of your school or district.

Three Questions to Shift Onboarding Beyond Orientation:

- How might we learn of the expertise that new staff brings to the work and share the expertise that already exists with them?

- What structures might we put in place to integrate new staff members into the culture of our school/district by networking our practice?

- How might we build a sense of ownership and mutual responsibility for learning design and outcomes?

How your team chooses to onboard staff sets the pace and tone for the rest of the school year for not only new team members but also for all those who interact with them. While there are a number of ideas and tools for onboarding, at the end of the day, small shifts in onboarding can add up to large impacts on staff success, retention, and belonging.

What mindsets are you shifting this school year?

Connect with Mira Education to jumpstart your onboarding practices. Let’s reimagine onboarding together.

For P20 education organizations seeking solutions to complex challenges, Mira Education is a proven design and implementation partner that applies a unique collective leadership approach to sustainable systems change to positively impact leading and learning.

Learn more about how we connect the dots among expertise and resources.

Prioritizing Teacher Agency: A Tool for School Improvement

Preparing students for success is complex work. Fortunately, we have found that teachers are ready and willing to take on the challenge of meeting the needs of this complex work alongside administrators. In fact, that is why many teachers entered the profession and continue to pioneer new approaches to learning. Teachers lead classrooms every day and seek to continuously learn and grow in their profession.

Even a decade ago, one in four teachers indicated interest in leading beyond their classroom (MetLife, 2013). Professional autonomy remains a consideration for retaining teachers; a recent survey found that teachers cited the ability to influence decision-making at a school level as one of their considerations for professional satisfaction and retention (SC TEACHER, 2023). By tapping into educators’ talent, school and district administrators can leverage teacher efficacy and agency to better prepare students to succeed in an increasingly dynamic world.

The Collective Leadership Approach

These factors led the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE) and Mira Education to create the Collective Leadership Initiative (CLI) that explicitly supports the development of agency and leadership across teams that include teachers, coaches, and principals.

Collective leadership leverages the capacity of educators in many roles to accomplish complex leadership work, within and across schools. We know that collective leadership is moderately to strongly correlated to collective teacher efficacy and, thereby, student outcomes (Eckert, Morgan, and Daughtrey, 2023).

Through this effort, we have witnessed collective leadership positively impact student outcomes, teacher retention, and a number of other school factors. One CLI school, Walker Gamble Elementary, has gone from being designated as an underperforming, to receiving statewide recognition as one of South Carolina’s Palmetto’s Finest, to becoming a National Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Distinguished School. Importantly, the school continues to be a Title I campus, has not added new positions or hours to the schedule, and has not radically restaffed. Instead, its CLI team found ways to better connect the resources they already had within their building to meet student needs.

Other schools that have integrated collective leadership into how they approach their work report increases in student academic growth, student leadership, teacher leadership, positive responses about school environment, and decreases in discipline. Many are considered destination schools; when vacancies open, high quality teachers apply because they want to be a part of those teams.

Not only does collective leadership move the needle on some of the biggest challenges in education, but it creates space for leadership opportunities where teachers can exercise agency. Moreover, it signals trust in teacher professionalism. As Amanda Williamson, teacher at Walker Gamble Elementary said, “When you allow me to exercise agency and do what’s right for my students…I truly feel like I’m looked at as a trusted professional.”

So, what are some of the keys to building teacher agency and collective leadership? We suggest you begin with priority setting.

Priorities

Effectiveness over efficiency

Let’s be honest: collaboration is less efficient than agency without parameters, but collaboration done intentionally has a compounding positive impact. The hope of collective leadership is that collaboration — even if it takes longer and involves understanding the perspectives and thoughts of people who think differently — multiplies the expertise of the group and makes both collective and individual actions even more effective. When school and district leaders help groups understand the strengths of individual team members, outline roles and responsibilities, and clearly describe which tasks are collaborative and which tasks are independent, teachers are enabled to use their talents freely.

Through CLI, the SCDE has had to figure out the balance between what we insist upon – the requirements every school must meet – and what we assist with – the supports and experiences that are unique to schools. Where we’ve landed is that every school collects the same efficacy and conditions data, but individual schools can choose where to focus their improvement efforts and what additional data they will collect to show progress toward that goal.

Personalized over programland

In addition to prioritizing effectiveness, we must also prioritize a personalized approach toward improvement rather than a cookie-cutter solution. We share from experience that it’s easy as a systems leader to get stuck in “programland”. In programland, our theories of action sound like this: “If our organization invests in getting schools to implement the program with fidelity, then the strength of the program will help our schools improve.” Living in programland is easy and while many programs are evidence-based and effective, they can be costly. Furthermore, to be successful, programs often need both buy-in and consistency – a lofty goal in an already demanding profession. If we view teacher leadership and agency as a one-size fits all program, we run the risk of preparing teachers for leadership roles that may never materialize in their context.

So, if we want teacher agency to be sustainable, we must exit programland and model collective leadership with the schools and districts we serve. When shifting to collective leadership, we can start by listening and asking the questions teachers are most apt to answer.

- What specific needs is the school seeing?

- What are the leadership strengths of the faculty?

- What are the specific strengths and areas for growth in classroom instruction?

- What support or professional development would help teachers and administrators grow in their ability to improve the school?

We encourage districts and states to start small with a group of schools that are interested in growing the capacity of teachers. A book study on collective leadership or a commitment to collecting and sharing data around a problem of practice are great places to start. Our book, Small Shifts, Meaningful Improvement offers both case studies from CLI as well as tools for teams to pilot their own collective leadership approach.

Cost-efficient and continuous over costly and complicated

Collective leadership that integrates teacher agency is not costly or complicated. However, it can be difficult to implement because it takes time and focus. It takes time to craft the school calendar and schedule so that teachers and administrators have opportunities to collaborate. It takes discipline to focus resources and conversation on learning and teaching. It takes sustained effort to develop teachers’ leadership. It takes skill to build the trusting relationships between and among faculty, students, and families that enable growth. What South Carolina collective leadership schools are learning is that taking the time to create systems that grow teacher leadership is worth it.

What collective leadership does NOT take is adding another thing to educators’ already full plates. It requires rethinking how educators–together–approach the complex work of preparing students. Dr. Cassandra Bosier, Principal at a CLI participating school, puts it best: “The only thing I am adding is opportunity.”

When your priorities are effective, personalized, cost-efficient and continuous, you create space for collective leadership and teacher agency to thrive.

Ultimately, preparing students to succeed in our increasingly complex world is going to require that we leverage the expertise of all educators. Prioritizing efforts that build and leverage teacher efficacy that are effective, personalized, and cost efficient are key to ensuring the student outcomes that we need and support the teachers who do the hard work every day.

To learn more about CLI visit the SCDE website and for more collective tools and resources visit www.miraeducation.org/tools.

Bibliography

Jonathan Eckert, Grant Morgan & Alesha Daughtrey (2023): Collective School Leadership and Collective Teacher Efficacy through Turbulence, Leadership and Policy in Schools, DOI: 10.1080/15700763.2023.2239894

MetLife. (2013). (rep.). The MetLife Survey of the American Teacher: Challenges for School Leadership. Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED542202.pdf.

Starrett, A., Dmitrieva, S., Raygoza, A., Carti!, B., Gao, R., Ferguson, S., Quiroz, B., & Tran, H. (2023 November). 2023 Teacher Working Conditions in South Carolina Rural and Town Schools. SC TEACHER. https://sc-teacher.org/documents/twc-23-rural-and-town/

Doing More With Less: Preparing for the ESSER Funding Cliff

Next fall’s $190 billion federal funding cliff may be causing almost as many sleepless nights as the pandemic did. For superintendents and other K12 district leaders, early Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds were essential for one-time emergency spending. Later, districts spent more to address learning loss, staffing needs, and other capacity-building to support full recovery.

Assessments of learning loss and equity implications for communities suggest that full recovery from the pandemic is far from finished, even if ESSER funding is ending. It’s easy to build an argument that schools need more base funding to continue to hire and retain educators, restore long-vacant positions for counseling and other student supports, and provide intensive programs for targeted students.

But the reality is that districts and states will have to identify cuts with the end of ESSER funding. The sooner and more thoughtfully districts can begin planning, the better. Budget cuts are unavoidable, but district leadership teams can use this as an opportunity to focus on what is actually important. Four practices can make sure that the cliff doesn’t send you into a free-fall.

Take time to articulate priorities.

From paraprofessionals to the superintendent’s office, educators across all roles agree on one thing: they never have enough money or time. While it’s hard to make more of either, we can choose how we spend both. That means getting distinct about what is most important – not just what’s ideal or urgent – and putting all our energy and resources behind just those things.

The daily urgencies of our work can make it challenging to take the time to identify these top priorities, let alone articulate them for school communities. But it’s an essential first step. If we don’t know our priorities, we can’t protect them — and that means cuts will be felt even more deeply.

De-silo the decision-making process.

Defining “priorities” depends on your perspective. Meeting the needs of 30 individual students and determining what works at the district scale are and should be entirely different viewpoints for decision-making, even when they both seek to center learners’ needs. When those viewpoints aren’t reconciled, leadership teams tend to rely on a combination of mandates, roll-outs, and seeking buy-in to encourage alignment with tough calls.

While leadership requires those tough calls, it need not require tough talk.

The harder the decisions are — and cuts of this type will be very hard — the more important it is to communicate about priorities with others and not just to them.

In over a decade of helping school and district teams tackle challenging changes, our organization has never seen a single “roll-out” of an important decision work smoothly based on an announcement. Rather, it requires consistent and connected communication that links back to the priorities you’ve already discussed together.

The time spent to share ideas, ask questions, and seek input is significant, but it is much less time — and much less stressful time — than the time that leadership teams otherwise need to spend in contentious bargaining tables, staff meetings, public hearings, and press conferences.

Fight the epidemic of “program-itis.”

Even evidence-based programs with robust support from skilled educators can fall short of their promise for students and schools. And that can sometimes be the best-case scenario. Many, if not most, of the programs that districts and schools plan to implement, require extensive (and expensive) training for staff before they can get off the ground or demand total fidelity to work as promised.

Sometimes there are just too many programs to be done well. In one improvement leadership network we have supported, school leadership teams identified more than 30 programs adopted in relatively small elementary schools. When staff are struggling just to name all the programs they have in place, it’s a good bet that they are struggling to run them.

Programs should support students and educators – not the other way around. Budget cuts not only offer us the opportunity to trim away what’s not aligned with priorities and getting results, but also to think about what is really sustainable. No matter how much money you have to spend on potentially effective and helpful programs, too many of them create a deficit of time and energy that contributes to stress, burnout, and attrition while doing little for student learning.

Plan proactively.

K12 education continues to be asked to do more with less. The repercussions of cutbacks are real, as is the stress that these decisions place on district leadership teams and personnel. But we can buffer those impacts if we shift from a focus on scarcity, which engenders feelings of restriction and dread, and replace it with a planned focus on opportunities to shed that programmatic “clutter” in ways that help us serve students better in the long run.

Our book, Small Shifts, Meaningful Change, offers a protocol in Chapter 4 to help you bring all these ideas together to reimagine your resources as part of a single 90-minute meeting. You can find more free tools and discussion guides on Mira Education’s website or contact our team for advice and support.

3 Reflections to Lead School Improvement Planning

The end of the school year calls for both reflection and planning. In the midst of drafting master schedules and reimagining resources, school leadership teams must also take stock of what worked and what no longer serves their students and staff.

Assessing impact in the current year while also planning for the next can be overwhelming. It is even more so when you consider the increasing number of priorities that come with closing out the school year like standardized testing, setting the budget, and end-of-year celebrations – just to name a few.

There is an abundance of “how-tos” and “how-nots” when it comes to school improvement planning, but the expertise needed to make the right decisions for your school or district often lies within your team.

Use these three reflection prompts to unpack this school year and plan for the next.

1. At the beginning of the school year, what was the vision and goals for your students? For your team? How was that vision crafted?

A clear vision and strategy help orient your team and your shared work. Identifying a vision for both achievement and experience is paramount to shifting the work toward your desired outcomes. As you think about your vision for this last school year, recall how it was developed. Was it done alone or were others invited into the process?

By inviting others into the vision and strategy creation process, leadership multiplies. As the next iteration of the vision is developed, leverage the expertise across your team and across roles to increase the ownership of vision, strategy, and outcomes.

2. How did you support your team in the facilitation of this vision?

Supportive administration, whether on the district or the school level, is a key part of retaining talent and expertise. How leaders choose to not just involve staff in the vision and strategy but also support the work is pivotal for both retention and seeing that vision come to fruition. According to the EdWeek Research Center, of educators polled, having a more supportive principal/manager was the top reason they chose to stay in the profession.

As you reflect on this past year, what supports did you and other leaders offer to your team? Where could you shift your practice to be more supportive and attuned to staff needs?

3. How were capacity and resources aligned to support the vision and strategy for the year?

Capacity and resources are finite. That is a universal truth across education and across roles within each district and school. How you organize capacity and resources, however, can significantly impact the realization of your shared vision and strategy.

Consider how your team spent time this year. Was collaboration and planning time prioritized in the schedule? Was there space for cross-team learning? Time is just one of many resources you can leverage in support of your vision. Download our tool, Reimagining Your Resources, to facilitate a 90-minute discussion and recalibrate your resources to your shared vision.

As you dive into reflection, we invite you to extend that into team learning and discussion. Check out our book, Small Shifts, Meaningful Improvement, for additional tools and case studies on how to apply a collective leadership approach to your school improvement planning.

Planning for Shifts: 3 Approaches as ESSER Ends

Education was interrupted in 2020. From virtual learning to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), the COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant shift in the profession. In response, the federal government bolstered district budgets with COVID relief funds. Now, just four years later, district leaders must shift again as those funds come to an end. Before the next school year, they will make hard decisions around ESSER funding and must pivot to meet the needs of students and staff.

What is ESSER funding?

The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, commonly referred to as ESSER, is a federal program that gave districts nearly $190 billion in response to the pandemic. Districts have until the end of September to commit their share of ESSER funds and will have until January 2025 to spend them.

For some districts, ESSER funds allowed for new construction in response to growing communities. For others, it meant hiring more staff to support student needs. No matter where districts invested their funding, the time is coming for district leaders to make shifts in order to maintain momentum.

Planning for Shifts: 3 Approaches as ESSER Ends

Shifts in how districts and schools operate without ESSER funding are inevitable. Cuts are coming, if not already here. But instead of embracing a scarcity mindset, district and school leaders can proactively plan for change. These shifts won’t happen overnight and may be uncomfortable, but they present themselves as an opportunity to re-engage the people who make the work of districts and schools possible – educators.

1. Revisit Your Vision

In your leadership practice, how you approach vision and strategy is as important as the vision and strategy you set. Intentionally invite your team to help co-create the vision and strategy for next year. Though resources are shifting, what you decide as a team is priority will help you gain insight into where to make shifts.

At Manning High School, for example, after experiencing a year of growth, their team wanted to build on that momentum. In the 2023-2024 school year, they came together to rally behind a vision to Watch Achievement Rise or their “W.A.R.” cry to increase student outcomes. By engaging their entire school community in a vision of excellence, they saw a positive impact on report card metrics, discipline, attendance, and enrollment.

As you establish vision and strategy, use this facilitation guide to identify and connect with a range of team members and invite them into the decision-making process.

2. Reimagine Your Resources

After you’ve co-created the vision and strategy with your team, aligning resources is a critical next step to not only seeing that vision come to fruition but also sustaining shifts in your work. How you make strategic sense of existing programs and initiatives will allow you to let go of what’s no longer serving your team and make space for more of what is moving you closer to the set vision.

Walker-Gamble Elementary, an under-resourced school in rural South Carolina, has approached their resources in a way that centers teacher time and student outcomes. By making shifts in their master schedule, every teacher has at least five hours each week for professional learning and collaboration, 75 percent of students experience 1:1 instruction, and every student and educator sets data-informed personalized learning goals at least quarterly (Byrd et al., 2023). By making small shifts in their schedule and reimagining how they work together with their existing resources, Walker-Gamble received South Carolina’s top recognition for schools, the Palmetto’s Finest award in 2020.

Use this activity protocol to guide your thinking and reflect on existing programs and resources with your team. You will need up to 90 minutes for this work.

3. Embrace Fresh Perspectives

Finally, the work of leaders should not be done alone. As ESSER funding comes to an end, invite new perspectives into the planning and implementation of shifts in your shared work. By de-siloing the work to be done, your team becomes co-owners of your outcomes, strategy and vision, multiplying the leadership across your team.

In Richland County School District Two, district leaders are tapping into teacher expertise as part of the planning process for the next school year. To increase teacher engagement in decision-making, they have asked teachers to develop master schedules for the next year to center teacher capacity and time needs.

Creating change and improvement in schools and districts is complex, challenging work. Use this discussion tool with your team to gain insight into your work together.

From Planning to Action

As you prepare for shifts in the new school year, continue to engage your team in the design and implementation of solutions. You can find more free tools and resources on our website or contact our team for thought partnership and support.