The educators who taught and shaped me in my first years of schooling back in Detroit were Black teachers from the South, most of whom had been displaced by the South’s massive resistance backlash to the Brown decision. Along with the adults in my family, they gave me a love of education. That’s why as a new teacher in 1990, I was deeply troubled by the dissonance between those formative experiences and the stereotypes in popular culture (and within my teacher education program) of Black students as perpetually at-risk of academic failure, along with caricatures of Black educators as inherently inept. Networking with other teachers helped me confront those stereotypes and changed the course of my own career.

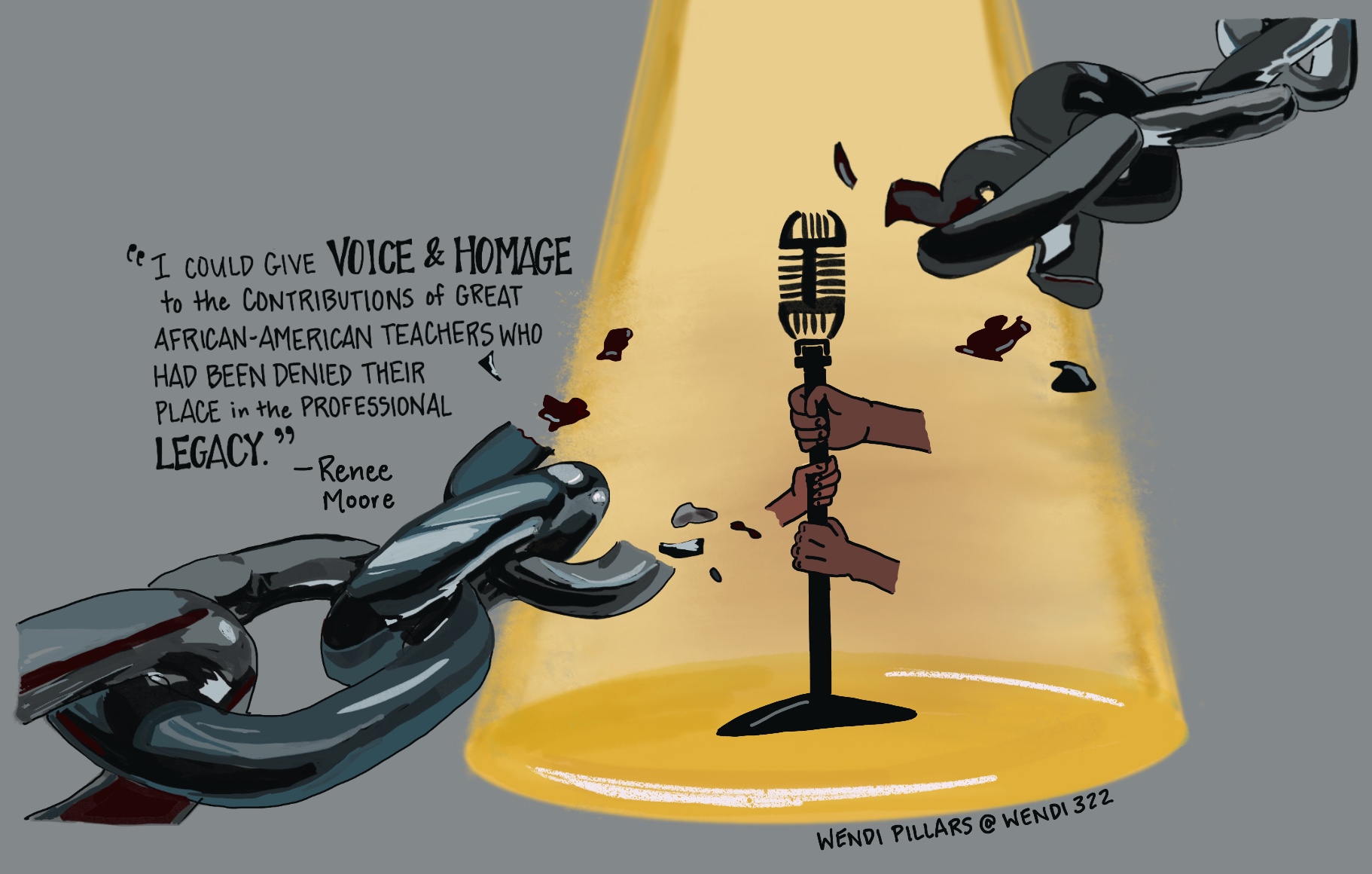

Network connections have paralleled my teaching career and propelled my growth as a teacher leader. About four years into teaching, as part of my graduate work through the Bread Loaf School of English, I helped pioneer the use of online exchanges to develop literacy skills among rural students via what was known then as the Bread Loaf Rural Teachers Network (BLRTN). Bread Loaf also introduced me to classroom action research, launching what would become a ten-year self-study about the teaching of Standard English to African American students. That research led to invitations to share at various venues. These opportunities mattered because there I could give voice and homage to the contributions of great African American teachers who had been denied their place in the professional legacy.

By the late 1990s, I was active in multiple teacher networks. One day I was invited to join the newly formed Teacher Leaders Network (TLN) sponsored by the Center for Teaching Quality, now Mira Education. Through TLN, I began my education blog, TeachMoore, and started working on Teacher Solution projects, tackling issues such as performance pay and teacher preparation. My participation in TLN and other networks also increased my opportunities to work with various groups addressing educational policy.

However, even years of professional accomplishments did not count when it came time to make the decisions that affected my own school and students. At one crucial juncture in my local school district, despite our students’ rising test scores, graduation rates, and college enrollment rates, the district hired a white consulting firm. The other teacher leaders and I were not just ignored but ordered to implement generic classroom practices from people unfamiliar with our students or our community. The high-quality, culturally-appropriate curriculum guides we had developed over two years (much of it on our own time) were discarded. The consultants were given the authority to monitor our classrooms and make sure we were teaching from the scripts they had given us. I share this cautionary tale because I’ve heard too many such stories from teacher leaders, especially from teachers of color, around the nation.

During this period, teacher networks were blooming, particularly on social media. Many were subject or location-specific, but most were true grassroot developments of teachers, particularly teacher leaders, trying to find each other and informally overlapping in membership and purpose. I think the growth was fueled by the joy of finding access to like-minded folk, or colleagues willing to share and listen.

I realized there were two significant differences between my highly accomplished African American teacher predecessors and me. Under the system of legal segregation, Black teachers (who were concentrated mostly in the South) had developed an extensive, sophisticated professional development network centered around the Black teacher associations (reverently referred to as “The Association.”) I had heard of this network and experienced its pedagogical products, but I entered the teaching profession after its dismemberment. The other difference between my highly accomplished mentors and me is that I have had access to venues and opportunities formerly closed to Black teachers, thanks primarily to their sacrifices and struggles. I vowed to use the platforms now opened to me to challenge the racist misperceptions of African American educators and our students.

A crucial step in that direction was the 2014-16 collaboration between Mira Education, the National Education Association (NEA), and the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) to develop a social justice curriculum that eventually became part of the NEA’s Teacher Leadership Institute (TLI). While helping to develop and teach that curriculum, I witnessed the powerful potential of uniting three teacher networks (of which I was part) around specific work that would directly impact student learning and create more equitable learning environments for potentially thousands of children.

Black educators’ work and voices are still blocked at many levels. I risked censure or worse for my research and teaching practices which unapologetically built on the work of distinguished Black educators and researchers. Yet, my limited work on national and state levels suggests that one Black teacher from the Mississippi Delta can have some impact on policy and teaching. Imagine what an engaged network of such teachers could accomplish for the profession, for students.

It is significant that many of the most vibrant teacher networks and movements of the past decade, such as EduColor, had at their core people who crossed paths via the Teacher Leader Network and Mira Education. The networking of networks not only amplifies the work of those who are already teacher leaders but the healthy (often challenging) cross-pollination helped produce more leaders and networks. Networking with other teacher leaders and helping to mentor new ones has also provided critical leverage against marginalization and isolation, especially for those of us in rural settings.

Teacher leadership still remains widely underutilized and unrewarded in most school systems. However, unlike when I started teaching, we now have a generation of educators who believe becoming highly accomplished teachers, and teacher leaders are normal career expectations. It is also assumed that teacher leaders should intentionally grow in cultural proficiency and develop as advocates of social justice within their schools. Due in part to the work of teacher networks over the past twenty years, other Black teachers and I are reclaiming our pedagogical heritage and re-asserting its value for broader educational policy and teacher preparation.

To paraphrase the song “I Remember, I Believe” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, I do remember the struggles and contributions of my pedagogical elders, and I believe their work prophetically points us to how the teaching profession should look.